Longitudinal Study of Ageing: Health Effects of Renting

14 July 2017

Dr Bram Vanhoutte of the School of Social Sciences, and his colleagues have studied the 'housing careers' of 7,500 people in England over the age of 50, asking where people lived from birth until the age of 50.

They found that owned housing is not only an indicator of material wealth, but equally makes a house a home, by providing psychosocial benefits in terms of housing security.

"Tenure is important not only in the here and now, but has long term effects on wellbeing, ” said Dr Vanhoutte. “For older generations renting for longer is linked with lower wellbeing in later life, underlining the need to increase the availability of safe, affordable and high quality housing for the many. Housing policy now will have a tangible influence on people’s wellbeing in the future."

Their study shows living in rented accommodation for longer, or owned accommodation shorter, is linked with more symptoms of depression, and lower subjective quality of life in later life. Examining the effects of moving home on wellbeing at various stages of life, they conclude that moving as a young adult for example is positive (usually linked to education, a career, or starting a family), whilst moving in midlife is usually a consequence of negative events such as divorce or separation.

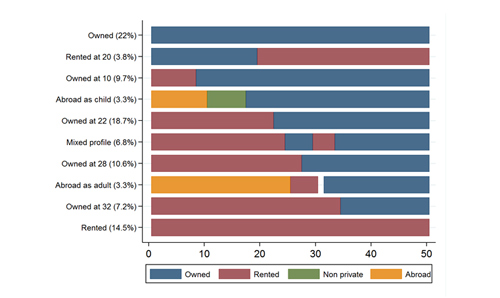

The research team identified ten different types of housing career, shown in the graph illustration which demonstrates for each year between birth and 50 in what type of accommodation they were living. Around 22 percent always lived in owned housing, and more than 14 percent rented all of the first 50 years of their life but there are marked differences in types of housing careers. Substantial groups of people move into owned housing after renting, either in their childhood, twenties or early thirties. Some more specific housing histories emerge as well, with people growing up in owned housing but renting for the rest of their observed career, or growing up abroad, and either come to England in their youth, spending time in non private accommodation such as boarding schools, or come back in their twenties, rent for a couple of years before living in owned housing.

There are real concerns about how these housing histories will impact later life wellbeing. The worst possible housing career for later life wellbeing was found to be those who rent for life, as well as those who grow up in owned housing, but then rent, a housing career that in a sense reflects downward social mobility, or at least the inability to sustain the same housing standards as in early life. Both types of housing careers are becoming increasingly dominant for current generations, and highlight just how crucial Dr Vanhoutte’s point is on the need to increase the availability of good quality affordable housing.